France, despite its reputation as a beacon of progressive liberalism, has been at the forefront of a burgeoning pan-European far-right movement.

Marine Le Pen, an anti-immigration Eurosceptic who may well top the first round of France’s presidential election on 23 April, is riding a populist insurgency that has been growing over the past 15 years.

Its themes are familiar in the era of Donald Trump and Brexit: concern for hardworking people, support for traditional values, and opposition to immigration and supranational busybodies.

But the most distinctive characteristic of France’s patriotic surge is youth. Unlike their contemporaries in the US and the UK, the under-30s in France are more nationalistic than the general population.

At the radical end of the movement are the “identitaires”, or identitarians – the equivalent of the American alt-right.

Who are the identitarians?

Their standard bearers are Génération Identitaire (GI), a group that specialises in publicity stunts that it films and posts online to advertise its fight to reclaim French territory said to have been lost to foreign migrants.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPGI has 120,000 Facebook fans – almost twice as many as the youth wings of the Socialist Party and the centre-right Republicans combined.

Unlike the skinheads of old, the group sticks to non-violence. The iPhone, it has found, is mightier than the boot.

France votes: on the BBC

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES- Is Marine Le Pen far right?

- Macron: Ambitious man on the move

- One-time favourite devoured by ‘fake jobs’ affair

- Fillon payment inquiry: What you need to know

- Who are the candidates?

- Inside France’s young far right

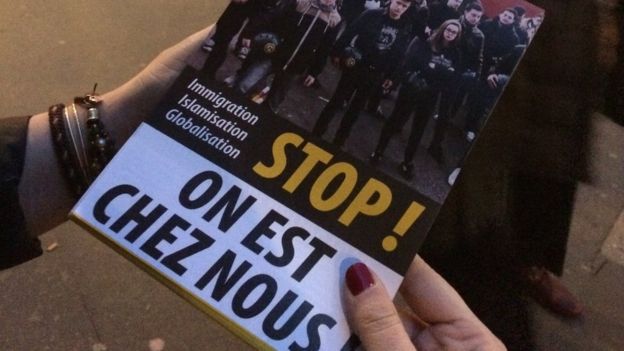

Following a group of activists handing out flyers in Paris, however, it is clear that they relish verbal confrontation. Their leader Pierre Larti, 26, stands surrounded by a group of North African men.

“When I read this leaflet I understand that you don’t want me here,” one says.

“What we don’t want is the replacement of our values by Islamic ones,” replies Mr Larti. “France is historically a Christian country. I’m not criticising anyone. What happens in your land is your business. What happens here is ours. We are against colonisation, and this is why we don’t want the same phenomenon to happen in reverse.”

Oddly, perhaps, for a group passionately attached to national differences, GI is sprouting branches across Europe. But identitarians see the whole continent as a battleground between European and Islamic culture.

Jean-Yves Le Gallou, a former Euro-MP, speaks of a struggle for “civilisational” identity. “Whether you are Dutch, German or French,” he says, “you have the same problem and have the same view of the world.”

Mr Le Gallou, 69, has produced a video entitled Being European (“Europe is not a globalised, borderless space. Europe is not African or Muslim territory.”) that has been viewed more than 3.2m times on YouTube in less than two years – three times as many as Being French, a sister video extolling his homeland.

Mr Le Gallou’s website, Polemia, stands at the high-brow end of France’s identitarian spectrum. In the 1970s, he was a leading member of the Nouvelle Droite, an influential group of far-right thinkers.

His continued influence is testament to the deep intellectual roots of the identitarian movement.

It also highlights the power of new media. Without the internet, Mr Le Gallou and others would have no mass audience. Their warnings against the “Great Replacement” of locals by immigrants are no-go areas for mainstream journalists.

Spreading the message online

Shut out by traditional media, identitarians have thrived on the web over the past decade. One of the online stars is Fdesouche, a news aggregator that features links to articles and clips from mainstream sites selected to chronicle chaos in migrant suburbs.

Fdesouche offers no comment, but leaves readers to draw their own conclusions: Islamists and “racaille” (“rabble” – code for dark-skinned criminals) are threatening to take over the country, one housing estate at a time.

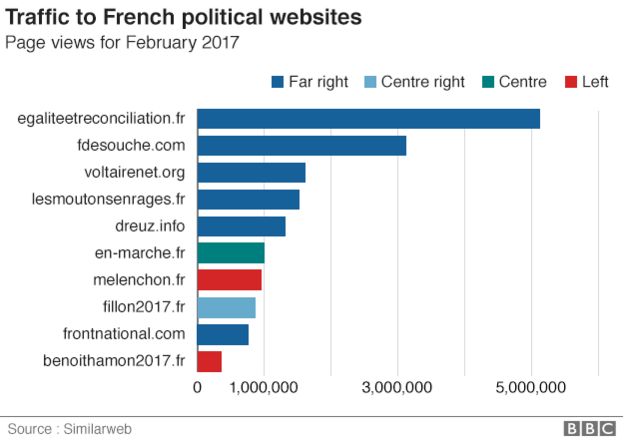

Fdesouche gets about 3m views per month, dwarfing the websites of mainstream politicians. Emmanuel Macron, a centrist with a devoted following of hipsters, manages less than 1m.

Fdesouche’s success has spawned a swarm of imitators and rivals.

Is France’s online far right a threat to democracy?

Often collectively called the “fachosphère” (from “fascist”), websites denouncing mass immigration and Islam have seen spectacular growth in France over the past 10 years. And France’s cyber-patriots are a diverse lot.

Read more here from Henri Astier’s investigation

One fault line divides new-model identitarians, who view Muslims as the main threat, from traditionalists who believe the chief malevolent force in the world is “Zionism”.

The most prominent anti-Zionist is Alain Soral. His website, Égalité et Reconciliation (E&R), weaves nationalist and left-wing themes by calling for solidarity with people from poor countries.

Soral rejects accusations of “anti-Semitism”. He sees a clear distinction between “ordinary Jews” and what he calls the organised Jewish lobby, which he says is persecuting him.

He sympathises with native French people, but feels identitarians are focusing on the wrong target. By “inciting poor whites to turn against blacks and Muslims” they were doing the work of Zionists, he told the BBC.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPAlain Soral is regularly prosecuted for incitement. But he is no bit-part player. E&R has more readers than Fdesouche, and by some measures is France’s most popular political website.

Various parts of the online alt-right may be firing from different directions, but their target is the same: the political and media establishment.

Such resentment is not the preserve of the identitarian fringe, or of people languishing in neglected provinces.

Opposition to liberal elites and concern about the disappearance of borders are widespread, and increasingly being aired in the heart of Paris.

At Sciences Po, an institution that trains the next generation of government and business leaders. Eurosceptic students have set up a club, “Critique of European Reason” (CRE), to wage the fight where it matters.

Its leader, Nicolas Pouvreau, says the group has managed to “create a Eurosceptic safe space in an environment that remains hostile.”

I celebrated [the Brexit vote] by eating fish and chips all day

Another member, Sarah Knafo, says the rising popularity of Marine Le Pen’s National Front (FN) – France’s largest party – has earned the group a grudging respect on campus: “We represent something bigger than us, and people dare not despise us as much as they used to.”

Last year’s Brexit vote in the UK thrilled CRE members. The next morning they gathered outside the UK embassy to drink champagne and sing God Save the Queen.

Anti-white racism

Beyond hostility to the EU, CRE members regard uncontrolled migration and trade flows as a source of social disintegration.

It would be wrong to label Critique of European Reason as far-right. The group brings together one-nation activists from both the left and the right who have much more in common with one another than with the moderates in their respective camps.

Kevin Vercin, another CRE student who supports hard-left presidential candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon, is as hostile to multiculturalism as the conservatives within the group.

Having lived in an immigrant banlieue (suburb) he says he has often been called “dirty white”, and says the mainstream press denies the reality of “anti-white racism”.

I used to go to school with fear in my stomach. You start to feel bad about being white, about being French and loving your origins because you get beaten up

Unfashionable as they are, these feelings are widespread among those who have left the banlieues.

“I have suffered from being white,” says Hugo Iannuzzi, a Sorbonne student.

“I have often cried. I used to go to school with fear in my stomach. You start to feel bad about being white, about being French and loving your origins because you get beaten up, your phone gets stolen and glasses smashed.”

Mr Iannuzzi supports the FN. But his resentment of the political and media elites mirrors that of left-wingers like Mr Vercin.

Lost generation

Alexandre Devecchio, a journalist and author of a book on various tribes of young French rebels, calls all those preoccupied with the erosion of identity the “Zemmour generation”. Eric Zemmour is an influential writer-broadcaster who argues that the 1968 revolt has led France to ruin.

Many of today’s twentysomethings, Mr Devecchio argues, agree with Zemmour because they feel let down. Born after the fall of the Berlin Wall, they were expected to blossom in an open, rainbow society within a pacified, post-historical Europe.

“For that generation, reality did not follow the script,” Mr Devecchio told the BBC. What they have experienced is unemployment, insecure jobs, and a sense of physical and cultural insecurity in areas where radical Islam is on the rise, he believes.

Could the identitarians and the wider Zemmour generation help Marine Le Pen win power?

At the moment that appears unlikely. Ms Le Pen lacks the backing of a major party, and is expected to be defeated by any second-round opponent.

But she can draw comfort from the fact that polls have underestimated the support of other populist leaders.

High abstention levels could also help her. The instinct to rally around whoever runs against the FN is much weaker now than in the past. Polls suggest that half the voters backing hard-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon would either abstain or back Ms Le Pen in a second round against Emmanuel Macron.

And should she lose the race, the setback could be temporary if her victorious opponent fails to bring about reform.

Identitarianism feeds on pessimism. The country’s patriotic rebels are young and may have time on their side.

[“Source-bbc”]