/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/56527223/620466077c427f141effa294382f5fba_XL.0.jpg)

Imagine if a well-paying job, with benefits and a high enough salary to pay for rent, transportation, and food, were a human right.

Imagine the US federal government established a policy whereby anyone who didn’t have a job and wanted one could go into a local office for a government agency — call it the Works Progress Administration — and walk out with a regular government position paying a livable wage ($15 an hour, perhaps) and offering health, dental, and vision insurance, and retirement benefits, and child care for their kids.

Different people would do different things: teaching or working for after-school programs or providing child care or building roads and mass transit or driving buses and so on. But everyone would be guaranteed a job, including during recessions. Involuntary unemployment would be a thing of the past. No one who works would be in poverty.

That’s a truly radical policy idea. But it has deep roots in the Democratic Party’s past, from the New Deal’s emergency employment programs to the Humphrey-Hawkins Act, a 1970s proposal that, as originally written, would have given unemployed Americans the right to sue the government.

Today, there are even some actual proposals on the table. In May, the Center for American Progress issued a report calling for a “large-scale, permanent program of public employment and infrastructure investment.”

But some labor economists, even left-leaning ones, are skeptical. None of the programs, they argue, have done enough work on the details. And those details are crucial to the eventual fate of such a policy.

An effective job guarantee that eliminated unemployment and boosted wages without negative side effects could be a very good thing. But an ineffective job guarantee that amounts to a welfare check plus onerous work requirements wouldn’t just be bad policy — it would also be politically toxic.

Why liberals are flocking to job guarantee plans in 2017

It might seem strange to be debating how best to solve mass joblessness at a time when the US unemployment rate is 4.3 percent, the lowest in over a decade.

And indeed, analysts critical of the plan raise exactly that objection: “Advocates who imagine we need a major restructuring of the entire economy are utopian and dystopian all at once,” says Adam Ozimek, an economist at Moody’s Analytics. “They are utopian in that they imagine we can nationalize a quarter of the labor force without significant negative effects on productivity and economic growth. They are dystopian in that they imagine things are so terrible that this kind of radical transformation is necessary.”

But there are both political and policy reasons for why the job guarantee is suddenly a hot topic.

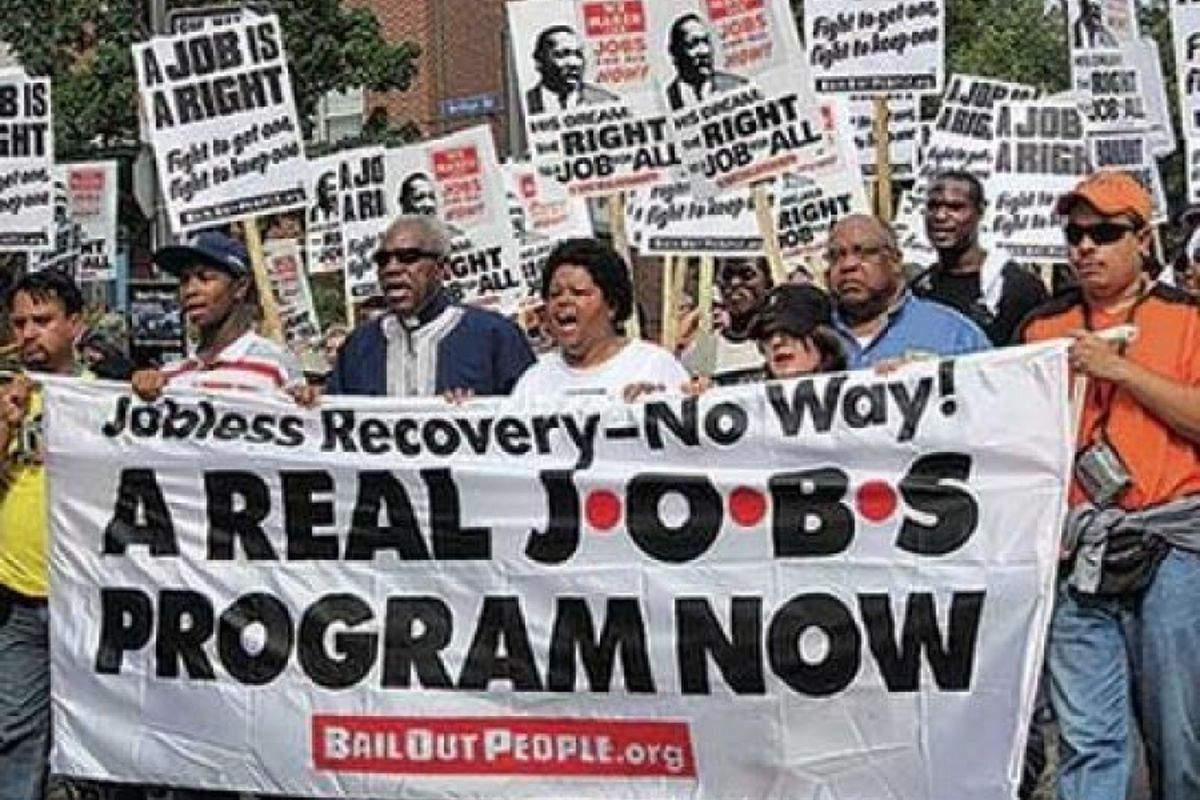

In the wake of the 2016 election, liberal commentators have latched onto the job guarantee — an idea pushed by some left-wing economists for years — as a way to forge a cross-racial working-class coalition. They need a plan that appeals to both to the white Wisconsin and Michigan voters who switched from Obama to Trump and to black and Latino workers left behind by deindustrialization. The ideal plan would both improve conditions for lower-income Americans while supporting Americans’ strong intuition that people should work to earn their crust.

“A federal job guarantee is both universal—it benefits all Americans—and specifically ameliorative to entrenched racial inequality,” Slate’s Jamelle Bouie notes.

“The job guarantee asserts that, if individuals bear a moral duty to work, then society and employers bear a reciprocal moral duty to provide good, dignified work for all,” Jeff Sprossadds in the influential center-left journal Democracy.

“If Democrats want to win elections, they should imbue Trump’s empty rhetoric with a real promise: a good job for every American who wants one,” writes Bryce Covert in the New Republic. “It’s time to make a federal jobs guarantee the central tenet of the party’s platform.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9161417/131430_16320.png)

But there’s also a policy rationale for the idea’s resurgence. Many experts think the unemployment rate makes the economy, or at least the labor market, look better than it really is. The unemployment rate only counts people looking for work, and the most recent recession and slow subsequent recovery forced some people out of the labor force. In January 2007, 80.3 percent of people ages 25 to 54 were employed; in July 2017, only 78.7 percent were.

If the rate had stayed at its prerecession peak, there’d be 2 million more people employed today. If the rate were at its all-time peak (81.9 percent, in April 2000), there’d be 4 million more people employed.

It’s possible those people will get jobs as the economy continues improving, but it’s not a sure thing. For one thing, the Federal Reserve keeps raising interest rates, a move that effectively kills jobs. There are also other factors at play. For decades, in both good economic times and bad, the share of men who are either working or looking for work has been declining. The labor force participation rate for 25- to 54-year old men fell from 98 percent in the 1950s to 88 percent today, per a 2016 report by White House Council of Economic Advisors members.

And it’s not just a matter of jobs. Wage growth has been somewhat anemic. During the last great boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s, wage and salary growth in the private sector, before adjusting for inflation, was about 3.5 to 4 percent per year, sometimes even topping 4, according to the Employment Cost Index. In recent quarters, however, wage growth has hovered around 2.5 percent. That’s slightly worse than things were in the mid-2000s, before the housing bubble burst.

Nor has the recovery been evenly shared. As of July 2017, 60.4 percent of white people in America were employed, but only 57.7 percent of black people were. Once black men’s disproportionate representation in prisons and jails is accounted for, the gap grows still larger. A mere 27.7 percent of disabled people age 16 to 64 are employed, compared to 72.8 percent of nondisabled people.

The bottom line is there are millions of people in the US economy who could be working, but aren’t. A jobs guarantee diagnoses that as a problem of demand: Private employers aren’t doing enough to make use of the US labor force. And it seeks to create such demand directly, by creating a new employer to provide it.

Have a disability, and unable to find an employer who will provide the support necessary for you to work? Well, under a jobs guarantee, the government would function as just such an employer. Lack a high school or college degree? A jobs guarantee could offer you a stipend to gain more training; if you don’t want to retrain, it could provide a skill-appropriate position that pays a living wage.

India’s successful job guarantee

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9161525/5103636919_7158632d80_o.jpg)

Job guarantee advocates argue it wouldn’t just affect people who take jobs through the job guarantee program. It would affect everyone else too. Walmart pays its employees a minimum of $10 per hour; part-time employees aren’t guaranteed benefits like health insurance or a 401(k) match.

If you’re a part-time employee at Walmart, and all of a sudden you can get $15 an hour, work full time, and earn full benefits by working for the federal government — wouldn’t you? And, knowing that, wouldn’t Walmart try to increase wages to keep you?

Advocates say Walmart would. And they have some empirical evidence on their side from India, where a type of job guarantee known as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme functions largely as an insurance system, offering a source of income for rural farmers during the dry season.

A group of economists — UC San Diego’s Karthik Muralidharan and Paul Niehaus and the University of Virginia’s Sandip Sukhtankar — collaborated with the former Indian state of Andhra Pradesh to randomize the roll-out of a new biometric card for participants in the rural employment program. The technology greatly improved access, but some subdistricts of Andhra Pradesh were randomly selected to benefit from it earlier than others. This randomization let the economists estimate the program’s effects by comparing subdistricts that got much-expanded access to the job guarantee to ones that didn’t.

Their findings are astounding: the job guarantee, they estimate, increases earnings for low-income households by 13.3 percent. Ninety percent of that increase is due to higher wages and increased work in the private sector, not the job guarantee program itself. Just as job guarantee advocates would predict, the program bid up wages everywhere.

Perhaps the most surprising result was that the program not only increased wages, but increased employment in the private sector.

Two things could be going on here, according to Paul Niehaus, the UCSD economist who co-authored the study. One is that employers in India are so few in number that they have more power to set wages than is typically the case, a phenomenon known as monopsony power. Under monopsony, firms typically have a number of vacancies, since to fill them they’d need to raise wages not just for new workers but for existing workers too.

Setting a minimum wage, either by statute or through a job guarantee plan, effectively forces the firms to pay more to everyone, which in turn drives more people to apply to work there, and fills the vacancies.

Alternately, Niehaus notes that private sector could increase because the program “created productivity enhancing assets,” like roads. The work done in the program could actually be useful in a way that boosts productivity and employment across society. Other research has also found that the program increase entrepreneurship by injecting cash into rural communities that workers can then use to start their own ventures.

How an American job guarantee could work

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9161533/488834318.jpg)

Obviously, though, the Indian and American economies are quite different. The US has no need to provide jobs as a secondary source of income for agricultural laborers and subsistence farmers; a lack of capital for small enterprises isn’t a major factor holding back growth here. Instead, a US jobs guarantee would have to come up with a constant supply of useful jobs that enrollees with a wide array of skills could do — and jobs that can grow and shrink in number, as the economy booms and busts.

There are two big questions any program would have to answer.

The first is whether the goal is truly for the government to give everyone a job, or just to give more people jobs. The Center for American Progress is wrestling with that question right now: “Does the job guarantee translate to the government acting as an employer of last resort, or does it mean guaranteeing sustained public funding for a target number of jobs over and above what we already have?” asks Carmel Martin, the group’s executive vice president for policy. CAP isn’t sure yet.

As an illustrative example, CAP’s May position paper supposes that a public employment program should return the employment rate of prime-age workers without bachelor’s degrees to its 2000 level of 79 percent. That would require creating 4.4 million jobs and would cost, CAP estimates, about $158 billion a year. It would also still fall short of guaranteeing every American a paying job.

A recent detailed plan from economists William Darity Jr., Darrick Hamilton, Mark Paul, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, is far more ambitious — it calls for employing about 14 million people at the cost of $775 billion per year, paid for in part by greater tax revenue, reduced reliance on safety net programs like food stamps, and lower incarceration rates. Wages would start at $11.56 an hour or $24,036 a year, indexed to inflation, plus another $10,000 a year in health care and retirement benefits. Participants would also get paid family, sick, and vacation leave. And the jobs would be guaranteed, not limited to a set number.

Still another outline from economist Pavlina Tcherneva, a professor at Bard College and its Levy Economics Institute, would also provide a guarantee, and allocate enrollees across nonprofit organizations rather than having the federal government provide jobs directly. While Tcherneva doesn’t go into this, such a plan would almost certainly amount to a massive subsidy to religious organizations, given how dominated the US nonprofit sector is by local religious groups and charities.

The second big question is what kind of work these workers would do. The Darity/Hamilton/Paul plan to employ 14 million people, for example, seems to envision pairing the guarantee with expansions to public services enabled by a larger government workforce.

Jobs, the authors write, could include child care work or teachers’ aides positions, and work for a new postal banking division of the Postal Service, established to provide an alternative to predatory payday lenders and check cashing services for poor households not reached by traditional banks. The plan offers little description beyond that.

Those are all pretty much permanent jobs. If a job guarantee were enacted in a recession, and many of the enrollees became child care providers, what happens when the economy improves and workers find jobs in the private sector? It wouldn’t be tenable to eliminate a universal child care program because the economy improved. Nor, if the program employed bus drivers, would it make much sense to cut bus routes. Either the government provides child care and runs buses, or it doesn’t; making how much child care it provides or how many buses are available dependent on the state of the economy would be odd at best and counterproductive at worst.

Infrastructure work, also included in the plan, could be a more appropriate area for job guarantee labor. While ideally we’d repair roads and bridges and rail lines as soon as they need it, in practice that rarely happens, and tying projects like those to economic trends might not be so bad. But implementing a real job guarantee plan would require thinking through how useful a large number of untrained workers would be for such projects and estimating how many could be productively put to use. Then, if that number is less than the stock of unemployed people during recessions, the government would still have to find other roles for people to fill.

A plan would also have to distinguish between different groups of people benefiting. For the long-term unemployed and young workers new to the labor force, more permanent positions might make sense, as their difficulty getting work isn’t necessarily tied to a bad economy. But for people struggling in a recession, the program might be more useful if it encourages work-sharing and deters layoffs, rather than pushing previously employed people into new jobs that they might not be a good fit for.

America’s last experience with public employment

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9161633/GettyImages_161984768.jpg)

At this point, a job guarantee is more a clarion call than a specific policy. No one has a bill that could be readily implemented tomorrow, or even in 2021. Rep. John Conyers (D-MI) comes closest with his bill, the Humphrey-Hawkins 21st Century Full Employment and Training Act, named after the largely failed 1970s bill pushed by civil rights activists and unions to enact a job guarantee. But Conyers’s plan isn’t particularly detailed, and leaves most of the implementation details up to states, local governments, not-for-profits, and other recipients of federal grants under the law.

Working through the details on the job guarantee is crucially important, especially for political survival. American history shows that even a mostly effective program can become politically toxic.

In the 1970s, amid economic malaise driven by the oil crisis, the federal government began funding job positions through the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). The program got some $47 billion in funding from its passage in 1973 to its dissolution in 1982; in 1977, President Jimmy Carter started directing more and more of that money toward public sector jobs, until by 1978 some 725,000 people had public sector jobs through CETA.

“CETA’s size,” Temple University political scientist Gary Mucciaroni writes, “dwarfed not only the employment programs of the 1960s but the entire War on Poverty effort.”

If you believe job guarantee advocates, the program should have been politically durable and popular, as it tied benefits to recipients’ willingness to work in the public sector and contribute to society.

It wasn’t. Instead, among its many opponents, the program became synonymous with corrupt liberal governance — a “visible symbol,” Mucciaroni writes, “of what its opponents argued was the futility and failure of government attempts to solve social and economic problems.”

“Like any government program, there were problems … but by and large it was a pretty successful program that got people employed quickly,” Carl Van Horn, a distinguished professor public policy at Rutgers and an expert on employment policy, told me. “But when Ronald Reagan was elected to succeed Carter, he announced that we had to get rid of this program … It was more about the symbol, of some people getting jobs to do things that weren’t perceived as worthwhile.”

And to be clear, some people with CETA jobs were doing things that weren’t worthwhile. Van Horn estimates that 5 to 10 percent of CETA projects were boondoggles or otherwise wasteful. But those projects are easy to publicize, and can be used to doom the program as a whole.

When the next recession hit, in 1981 to 1982, the worst downturn until the 2007 to 2009 financial crisis, the CETA program was so “radioactive,” as Van Horn puts it, that no one really proposed trying mass public job creation again.

“It also became intertwined with race,” Brown political scientist and sociologist Margaret Weir notes. Joblessness was seen as a black problem, and blacks were seen as primary beneficiaries of the public sector positions created by CETA in cities.

If CETA was effective but politically toxic, plenty of other public employment programs haven’t even been effective. While job guarantee programs envision a broad, inclusive program that can integrate all participants into the broader economy, the result is often a program that serves people who can’t get work anywhere else, and still can’t get work anywhere else after the program is finished.

Berkeley economist David Card recently conducted a meta-analysis of more than 200 evaluations of programs meant to boost labor markets, along with fellow economists Jochen Kluve and Andrea Weber. While they found a variety of impacts of different programs, one constant was that public employment programs that simply hired people directly performed worst.

“Public sector employment subsidies tend to have negligible or even negative impacts at all horizons,” the study concludes. “This pattern suggests that private employers place little value on the experiences gained in a public sector program.” One reason, they suggested, was that the programs did nothing to help build skills that would make participants more employable.

Job guarantee advocates counter that a well-designed program would get around these concerns. CAP’s Martin argues that sound design would both permanently increase public employment, meaning unemployability in the private sector isn’t a concern, and that it will involve training programs that can boost skills.

Margaret Weir also expresses hope that a universal job guarantee could be more politically viable than the 1970s public employment program. “The jobs problem is perceived as a white problem now,” she notes. “I think that local government and nonprofits are more capable/professional now than they were in the 1970s, and could more easily implement a jobs program.”

Van Horn, on the other hand, expressed skepticism, fearing the same factors could doom public sector employment this time around, especially America’s fundamental uneasiness with direct government intervention into the job market. “I’d say it’s more likely we’d have a single-payer health care system than a guaranteed job program, and that’s also a reach,” he says. “There’s a very long tradition in public policy and the history of this country that this is a lightly managed economy … The idea that the government would suddenly change after 200 years of not doing that, and certainly not in the modern era, I just don’t think it’s likely.”

All which means job guarantee advocates should be thinking seriously about the details. The experience with CETA is a reminder that the line between a brilliant idea and a political failure is narrow, and that funding even a handful of bad or bad-looking projects can easily doom a program.

After the initial energy for public jobs and even a jobs guarantee in the 1960s and 1970s, “the flurry of new programs,” Weir wrote in her 1992 book Politics and Jobs, “was followed only a few years later by disillusionment and a sharp scaling down of resources devoted to them.”

[“Source-vox”]