There is no shortage of cool new apps, from the one that turns your camera into an emergency flashlight, to the one that spontaneously materialises a taxi or groceries at your doorstep. Or the one that tracks your rapidly depreciating investments in real-time. As cool as these apps seem though, they are all probably spying on you.

Unscrupulous companies could make innocuous seeming apps that harvest your text messages, your contacts and call history, while potentially even sending texts and making calls you may never know about. They may even be using your phone’s camera to take photos or your phone’s microphone to record audio. And worst of all, if they are, it is because you let them.

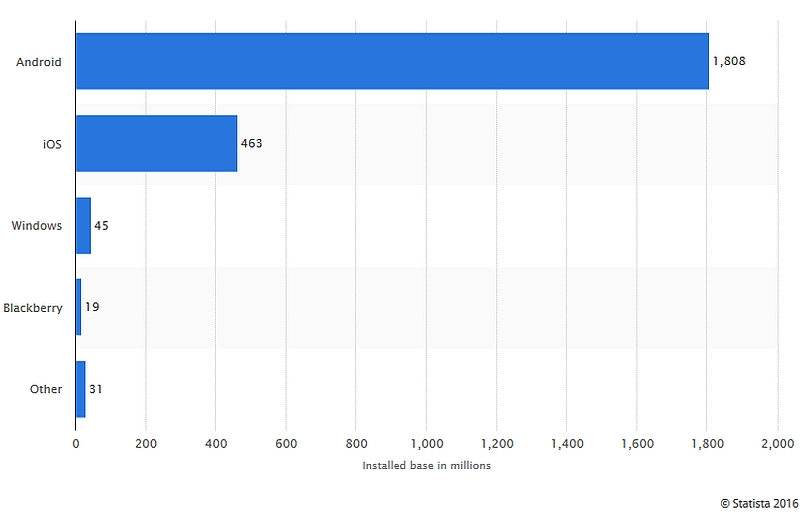

While the public conscience is occupied with technology-policy battle after battle – from net neutrality to the encryption policy to Microsoft-Ireland to Apple vs. FBI – the estimated 1.8 billion users of the Android operating system may have already lost a battle that has been as prolonged as it has been hidden from the public glare. And like many other battles in the technology realm, it concerns user data. Only this time it is not data stolen or secretly collected, it is data that you ‘agreed’ to hand over to companies on a platter.

What are Android ‘permissions’?

What are Android ‘permissions’?

Every time a user installs a new application on an Android device, they consent to certain ‘permissions’ being granted to the application. These ‘permissions’ allow apps to interface with the operating system to access information, use system resources, hardware and carry out different operations. For example, a cab hailing application would require permission to use a phone’s GPS receiver to acquire user location data to pass on to the driver and so on. These permissions are granted by users at the time of installation of a new application on most devices. Users accept permissions for apps much like they ‘agree’ to the End User License Agreements (EULAs) while installing software on Windows – in most cases, with nothing more than the most perfunctory glance.

Permissions are required to ensure that the app is able to function as advertised (to hail a cab, or purchase groceries or send a message). But if apps only sought permissions that were necessarily required to carry on core functions, there would be no debate. When an app meant to track the stock-market requires access to your phone’s microphone to record audio, questions must be asked.

A quick glance at the permissions granted to apps on my Moto G revealed that 27 apps had access to my camera, 57 to my contacts, 45 to my GPS location, and 20 to my microphone. Some obvious red-flags were the Moneycontrol and BigBasket apps being able to record audio through my microphone; BigBasket, PepperTap, and Grofers all can access my camera; and the HDFC app can access my GPS location – all without advertised uses for such kinds of data. While this does not mean these apps exploit, or even actually use these permissions, the onus must be on developers to clarify why each of the permissions is sought.

![]() This status-quo is all the more worrying due to the lack of transparency surrounding app permissions. In order to address such information asymmetry, developers must be incentivised to disclose the permissions their apps require and the reasons therefor. If an e-commerce app has the ability read all your contacts and acquire GPS data without any advertised reason for the same, it must be required to disclose what it plans to do with such data and, critically, if this access is required for core app functionality.

This status-quo is all the more worrying due to the lack of transparency surrounding app permissions. In order to address such information asymmetry, developers must be incentivised to disclose the permissions their apps require and the reasons therefor. If an e-commerce app has the ability read all your contacts and acquire GPS data without any advertised reason for the same, it must be required to disclose what it plans to do with such data and, critically, if this access is required for core app functionality.

Transparency must be a minimum requirement. With privacy becoming a criterion for product differentiation, it may even be in the interests of developers to offer clear disclosures.

Need for Awareness

In today’s information economy, harvesting user data for advertising may be an important – and even legitimate – revenue stream for developers, this trade-off must occur in a manner that is consensual. For that, the pre-requisite is not only transparency but also awareness. While Android does attempt to be transparent about permissions sought by an app (at the time of installation), users need to be educated about the risks of granting permissions which permit collection of sensitive data.

In the Indian context, with a number of individuals coming online for the first time, this need is further accentuated. First-time and experienced users alike need to be given an opportunity to understand the terms on which they are using a particular app. The lack of availability of disclaimers, terms of use, privacy policies and other documentation in local languages is another urgent issue on which progress is required.

In the Indian context, with a number of individuals coming online for the first time, this need is further accentuated. First-time and experienced users alike need to be given an opportunity to understand the terms on which they are using a particular app. The lack of availability of disclaimers, terms of use, privacy policies and other documentation in local languages is another urgent issue on which progress is required.

At the same time, all of this is not to say that there are no legitimate purposes for which sensitive permissions may be sought or granted. For instance, apps requiring payments may require the capability to scan incoming text messages in order to extract bank-generated one-time-passwords (OTPs) to facilitate two-factor authentication. But even in such cases, users must be able to opt-out and choose manual OTP entry over untrammelled access to their data. In addition, developers must provide detailed information on the extent of scanning/ processing activities – for instance do the activities take place only when the concerned app is opened, or are they always running in the background. Privacy trade-offs may be justifiable, and required, in the present day and age but this does not mean they should happen in a manner that user consent is vitiated by digital illiteracy, lack of technical competence or information asymmetry.

Law Enforcement

Broad app permissions also provide law enforcement with creative avenues to track down criminals or, alternatively, conduct mass surveillance. Given the lack of judicial oversight over user data requests in India, the latter is a more likely outcome. In any case, app permissions may present a new and unexplored avenue to conduct covert surveillance, investigate cybercrimes and exploit previously unavailable data points to nab criminals.

If not already the case, it is only a matter of time before authorities realise (to their benefit) that there may be Indian developers with access to as much actionable user data as their often-unreachable foreign counterparts. This could mean merely approaching an Indian app-maker whose app is permitted to place a call, send a text message, record audio or send GPS data. This presents a significant advantage over the broken MLAT procedure for requesting data from foreign companies. After all, who would suspect that your flashlight app was the one that got you busted?

If not already the case, it is only a matter of time before authorities realise (to their benefit) that there may be Indian developers with access to as much actionable user data as their often-unreachable foreign counterparts. This could mean merely approaching an Indian app-maker whose app is permitted to place a call, send a text message, record audio or send GPS data. This presents a significant advantage over the broken MLAT procedure for requesting data from foreign companies. After all, who would suspect that your flashlight app was the one that got you busted?

Postscript: Apart from efforts made by OEMs like Xiaomi and software vendors like Cyanogen to include permission managers in their software, with the latest version of the Android (Marshmallow or 6.0), users are provided with an easy option to revoke each permission granted to an installed app. In addition, users are notified each time an app requests the use of a sensitive permission for the first time. While an extremely positive development, this is not (yet) a complete solution. At the outset, Android 6.0 penetration accounts for around 2.3 percent of all Android devices in existence (as of March 2016) – a metric excluding a large number of devices for which Google does not maintain official usage statistics. While this number is set to increase over the coming months, a large number of users will continue to use previous Android versions for years to come. To get an idea of the permissions granted to different apps on your pre-Marshmallow phone, you can download, not without irony, another app – such as MyPermissions.

[“source-ndtv”]